Meet Colletes perileucus,

a southwestern US native found nowhere else in the world.

These bees are in the family Colletidae, and are called cellophane bees, plasterer bees, or polyester bees.

These common names refer to the natural plastic produced by female bees to line the insides of their nests!

A Colletes bee emerging from its underground nest.

Photo: Jtal via BugGuide

Photo: Carlos Martinez, UA Entomology

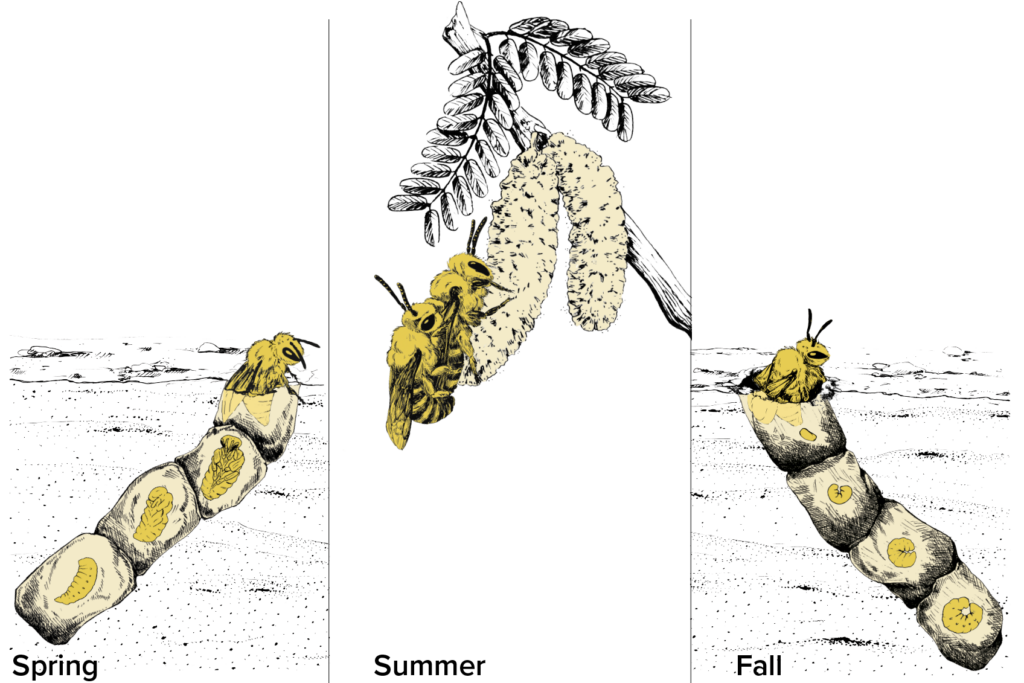

The season for C. perileucus begins in late spring, around the time mesquite begins to bloom.

Native bees collecting nectar and pollen from a blooming mesquite in Arizona.

Photo: Sue Carnahan from an iNaturalist observation.

In the spring time, if you look closely, you can observe returning mother bees with bright yellow and orange pollen attached to their legs.

A female Colletes perileucus — this pinned specimen is among many held at the University of Arizona Insect Collection.

Photo: Carlos Martinez, UA Entomology

Male bees tend to emerge before females, and wait outside of the nest to mate with a female as soon as she emerges.

Often, there are so many males interested in a single female that “mating balls” are formed, with many males surrounding a female in the center of the “ball.”

A mating ball of Colletes bees, where a single female is surrounded by multiple males.

Photo: beewatching.com

As a solitary bee, Colletes perileucus females are truly single mothers.

After mating, each female digs a subterranean nest, containing multiple “brood cells.”

Each brood cell contains an egg and food provisions that last her offspring until adulthood. Once her eggs are laid, she seals the nest, and her job is done.

Phenology or lifecycle diagram of Colletes, showing the hatching from brood cells, through mating to the laying of eggs. Illustration: Oona Husok, UA Entomology

At this time of year, many other insect mothers are also looking for places to lay their eggs.

You might see this “bee fly”, or Bombyliidae, flicking its eggs into the Colletes nests.

While this fly looks similar to the bee, it is actually a parasite, and its young feed off the developing bee larva inside the brood cell, eating it alive!

A bee fly looks very similar to a bee, and even flies like one; but it is an impostor! You can tell the bee fly from its short antennae, and that it only has two wings.

Photo: Joan Fox

At the Moore Lab of Arthropod Systematics, we study insects like the Colletes cellophane bees. We also study their interactions with other species, like their bee-fly parisites.

To study Colletes, students in our lab excavated 9 brood cells in July of 2024, keeping them alive over the next year, and opening one every two months to study their development.

The bee larva in this photo is estimated to be about a month to two months old. Once hatched from its egg, it begins eating the provisions within its brood cell.

Photo: Carlos Martinez, UA Entomology

We have erected a sign at a Colletes nesting site, right outside the Marley Building on the UA campus.

Please come and visit the Colletes bees to see them in real life and learn more about their life cycle.

They are most likely to be visible from mid-March until June; the rest of the year they are developing underground!

Interpretive sign project initiated by the Wendy Moore Lab of Arthropod Systematics, through the generous support of the UA Entomology Science Communication Endowment Grant.

Photo: Rafe Copeland

Colophon

Dr. Wendy Moore (Project supervisor)

Alex Lombard (Art and Project director)

Charles Bradley (Research Coordinator)

Oona Husok (Illustrator)

Tanner Bland (Project Coordinator)

Raine Ikagawa (Website Designer)